This Oscar winning film was a remake of the 2002 Hong Kong crime thriller Infernal Affairs, leading to a rarity in the industry – a remake outdoing the original. Martin Scorsese, the director, made a deliberate effort to not watch Infernal Affairs until after The Departed was completed. Instead, he used William Monahan’s script as the epicentre of his vision. Monahan’s script relocated the story to Boston, Massachusetts and gathered inspiration from the real Irish-American gangster Whitey Bulger and corrupt FBI agent John Connolly, combining this with the plot of the original Hong Kong film. Scorsese’s film has a 50 minute longer running time than the original, but this isn’t the only way it exceeds its predecessor; it possesses greater substance in the form of its thematic complexities.

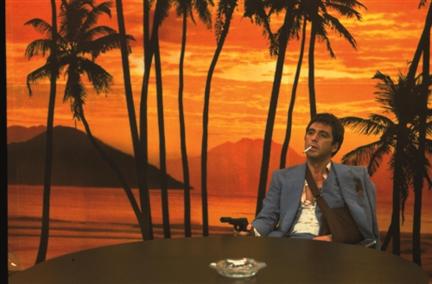

Scorsese has said this “is the first movie I have ever done with a plot’’. If this is the case, then I make the argument that he should do more. It follows Billy Costigan (Leo DiCaprio) and Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon), both characters beginning in the Boston police academy but once graduating they undertake opposing parallel paths. Costigan is assigned to go undercover and infiltrate Frank Costello’s (Jack Nicholson) Irish-mob syndicate. Simultaneously, Sullivan – who has been under Costello’s wing since his youth – works as an informer for the mob. Both men struggle with their double lives and the concept of identity is perhaps the central theme.

This was DiCaprio and Scorsese’s third collaboration together and it’s easy to see why they have established such a formidable partnership. DiCaprio’s Costigan is someone whose heart is filled with pain and head is enraged with anger. His family name isn’t the most honourable as many of his relatives are convicted. He joined the police force to shake off this degradation and become the good guy but, unable to escape, he is dragged into the criminal life. He is subjected to a tirade of abuse by Mark Wahlberg at the beginning and then ordered to intrude Costello’s mob. Costello being the complete incarnation of evil, the mission doesn’t sit well with Costigan, torturing his psyche. Costigan, in some ways, fits naturally into the mobster mould, being careless and violent. In other ways, he is the hero for the audience due to his determination and that’s the real testament of DiCaprio’s performance.

On the flipside is Damon’s Sullivan – the most complex character of the piece. Someone that appears to be the typical confident hero on the surface, possessing many likable qualities. In reality, his life is rooted in lies and the deception starts to haunt him. Damon portrays these complexities subtly and superbly. Sometimes so subtle you miss them, specifically his sexuality which you should give close consideration to when watching the film. DiCaprio is loud, brash but ultimately admirable whereas Damon is slick, smooth and deceiving. Two people who are lost in their identity.

Scorsese’s pedigree allowed him to attract a ridiculous cast, with many ‘leading-men’ performers taking supporting roles. Scorsese’s original vision was a low budget production but the budget soared as more stars became committed. Jack Nicholson becomes Costello in typical crazy Nicholson fashion. Costello is a truly menacing figure whose extreme violence and prejudices are always accompanied with a smile. Costello represents the entire evil entity of Boston – ‘’ I don’t want to be a product of my environment. I want my environment to be a product of me’’ is a line that stays in mind. Mark Wahlberg gives one of the performances of his career as foul-mouthed Staff Sergeant Dignam, his aggressive antics producing a lot of the film’s humour. Mentions also must go to Martin Sheen as Captain Queenan and Ray Winstone as Costello’s number two, Mr. French. Sheen brilliantly contrasts Wahlberg’s Dignam and at times acts as a father figure to Costigan. Winstone is convincing as a hard thug even if his Boston accent isn’t. Significant credit lies with Scorsese as he expertly balances the screen time of each performer and allows all of them the opportunity to showcase their talents.

Music is a recurring allure of many Scorsese films; The Departed being no exception. The film begins with The Rolling Stones’ Gimme Shelter – which has appeared in two other of his films – some may see this as overindulgence but it is perfectly suited to the rhythm of the opening scene when we are introduced to Costello. Music is also exceptionally applied during a love scene. The featured song is Comfortably Numb by Roger Waters, Van Morrison and The Band – starting off quietly to build sexual tension and then exploding into the chorus when it reaches boiling point.

One surprising common trait of epic police and crime dramas that Scorsese has not adhered to with this film is the use of city skyline shots to enforce the scale. Films such as Heat come to mind when thinking of thrillers that really use the huge landscape and architecture of the city to create an expansive space for police and gangsters to battle. It is often said the city becomes an important character in the story. Boston is as much of a character in The Departed as Los Angeles is in Heat but Scorsese uses different practices to create this sense of environment. He creates an atmosphere of claustrophobia, showing Boston as a close-knit community where all of the characters seem to be intertwined in some way, family history playing an important role. Costigan and Sullivan seem to be trapped in an intolerant city with their double lives taking its toll on them psychologically.

Verdict

The Departed should be the benchmark for the remake concept. It doesn’t remake the original in the traditional Hollywood framework of repackaging it for a new generation/English-speaking audience. It takes the general concept and expands upon it, elevating the themes and intensity as well as perfectly transitioning it to an American culture. It’s a downright thrilling experience seeing this A-list ensemble cast play out this complex escalating plot with interesting untypical characters. Possibly my favourite Scorsese film.